This post continues my earlier argument that systems thinking comes before analytical thinking. Systems thinking isn’t about slicing a problem into parts; it’s about seeing how the parts interact, adapt, and evolve as a whole. That naturally raises the question: what tools do we actually use to practice it?

Here’s the counterintuitive answer: systems thinking has no single, universal toolkit. It adapts across contexts and professions.

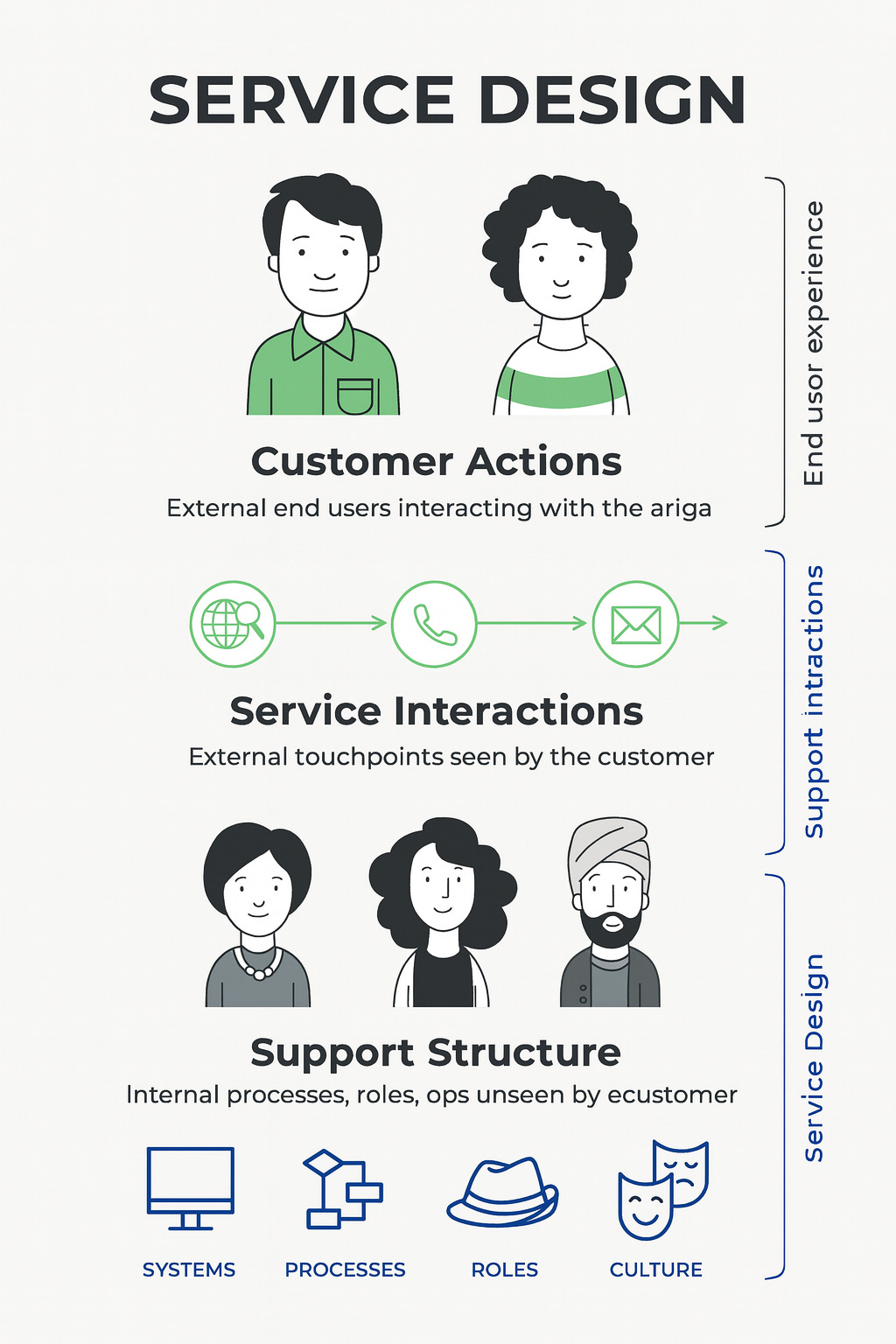

The World Economic Forum offers a helpful example from service design: a service blueprint—a map of customer interactions, frontstage touchpoints, and backstage processes—can function as a high-level way to investigate a “system of interest.” On the surface it’s just a process diagram; through a systems lens, it reveals interdependencies, feedback loops, and bottlenecks shaping the customer experience.

In project management, a causal loop diagram plays a similar role. It can look like a simple cause-and-effect sketch, but viewed systemically it exposes reinforcing and balancing loops that drive behavior over time. For example, adding resources to “save” a delayed project boosts coordination overhead, which slows decisions and creates more delay—a reinforcing loop you won’t see in a typical status report.

The key truth is this: the tool doesn’t make it systems thinking—the lens does. A blueprint in service design or a loop diagram in project management becomes powerful when it helps us see connections, patterns, and feedbacks that an analytical snapshot often flattens.

Four Themes that Give Systems Thinking Its Teeth

1. Interconnectedness

Systems thinking requires a shift in mindset, away from linear to circular. The fundamental principle of this shift is that everything is interconnected. Humans rely on ecosystems and infrastructures; technologies rely on supply chains and social systems. Inanimate objects like a chair or phone only exist because of countless upstream systems.

From a systems perspective, this mindset breaks us out of a mechanical worldview of isolated parts and forces us into a dynamic one—where feedback, relationships, and dependencies determine outcomes.

2. Synthesis

If analysis is about breaking things apart, synthesis is about putting them back together to understand the whole. Systems thinking is built on synthesis.

The power of synthesis is that it prevents optimizing subsystems at the expense of the whole. A team can deliver on time but overload downstream testing. A department can cut costs but destabilize the organization. Only synthesis shows the trade-offs across the whole.

3. Emergence

Emergence is what happens when the whole produces outcomes not predictable from its parts. Traffic jams, silo wars, or viral growth in networks are emergent behaviors.

Emergence is why systems thinking matters—because the most critical outcomes (project failure, cultural shifts, social tipping points) come from interactions, not components.

4. Feedback Loops

The beating heart of systems thinking is feedback. Reinforcing loops accelerate change, balancing loops resist it.

For project managers, this means some problems aren’t about finding the right fix but about recognizing the loop. A reinforcing loop can spiral into runaway collapse. A balancing loop explains why initiatives stall despite massive effort. Seeing feedback loops reveals not only what is happening, but why it keeps happening.

Together, interconnectedness, synthesis, emergence, and feedback loops give systems thinking its teeth. They force us to move beyond surface symptoms and into the deeper structure of how the world actually works.

A Practical Walkthrough: Step-by-Step Systems Thinking

Define the system of interest — What’s the purpose of this system? What problem keeps recurring?

Shift from parts to relationships — Focus on interactions, not just elements.

Look for feedback loops — Reinforcing (R) vs. balancing (B) dynamics.

Notice delays — Where does time separate cause and effect?

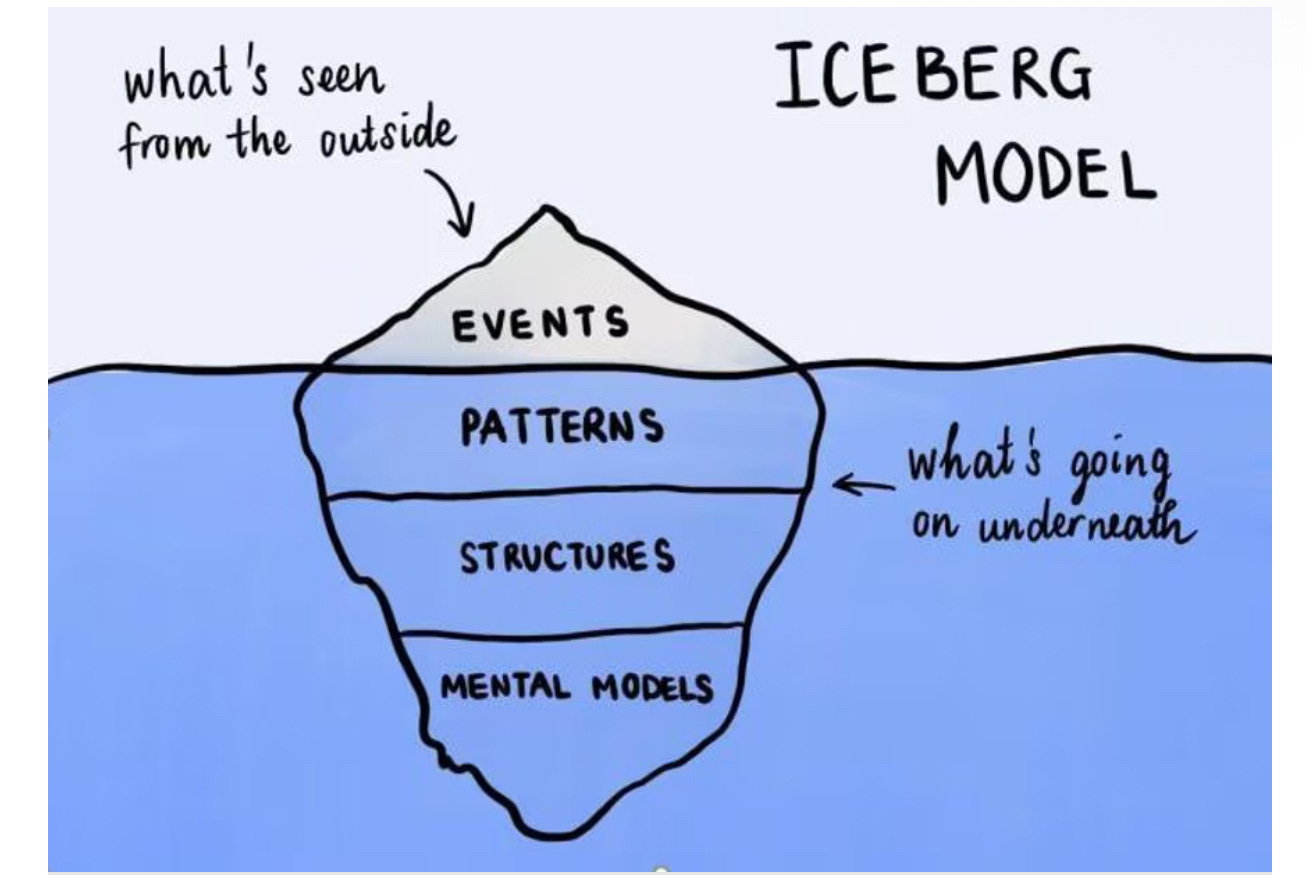

Surface mental models — Challenge the beliefs driving today’s decisions.

Find leverage points — Identify small changes with outsized impact.

Zoom out, then zoom in — Context first, then focus on pivotal loops.

Test and adapt — Try safe-to-fail changes and observe the system’s response.

Mini-practice: Pick one repeating issue in your work. Sketch the relationships, mark one feedback loop, and identify one leverage point you could test within two weeks.

(WEF image)

Benefits of Systems Thinking

Adopting a systems thinking perspective carries powerful advantages:

Big-picture clarity

Instead of getting lost in details, systems thinking highlights interconnections and dynamics, revealing where critical linkages shape outcomes.High-leverage interventions

By mapping archetypes and feedback loops, systems thinkers can identify points where small changes cascade across the system, preventing wasted effort on surface-level fixes.Anticipating long-term consequences

Tracing reinforcing and balancing loops exposes secondary and tertiary effects of actions—helping avoid unintended impacts that ripple over time and space.Order within complexity

Systems thinking surfaces underlying patterns that cut through complexity, providing structure and coherence without oversimplifying the messy reality.Strategic foresight

Conceptual tools like stocks and flows reveal the hidden structures that drive recurring outcomes, enabling leaders to design forward-looking strategies.

In all of these ways, systems thinking empowers more responsible, adaptive, and transformational decision-making. It equips leaders to navigate complexity with foresight, align interventions with real-world dynamics, and spot opportunities where others only see confusion.

Other Voices in the Systems Space

The WEF blueprint example and project-management loops sit within a broader conversation. For additional perspectives, explore work from:

Systems Thinking Alliance and Pegasus Communications (practical training and forums).

OECD and IIASA on systemic thinking for policy.

Professional societies such as ISSS, IFSR, INCOSE, and IEEE SMCS advancing systems science.

Harvard Business Review (HBR), often framing business challenges through a systems lens.

FSG, applying systems thinking to social change.

Journal of Systems Thinking (JoST), open-access peer-reviewed research.

Call to Action

Where have you seen emergence in your own projects—a result that couldn’t be predicted by looking at the parts alone? Share your thoughts in the comments.

If this exploration was useful, subscribe to PM Researcher for more frameworks and tools that connect systems thinking with strategy, decision-making, and project leadership.

Hope this helps.

Nicole

References

HBR.org/2025/09/why-you-need-systems-thinking-now

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2021/01/what-systems-thinking-actually-means-and-why-it-matters-today/

https://www.coursera.org/learn/systems-thinking-basics

https://www.coursera.org/articles/systems-thinking

https://www.coursera.org/learn/systems-mindset

I love the reminder that systems thinking isn’t about the tool, but rather the lens applied. Also a huge fan of the iceberg model. Great post.

I really appreciate the systems thinking approach, and I agree that it’s ultimately about the perspective you bring to the problem. Still, once things get complex, having the right tool or visualization method can make a huge difference in understanding the dynamics at play. That’s why I wouldn’t underestimate the impact of using the right tool—it can often shape not just the clarity of the process, but also the quality of the results.